Jack Tempchin is a product of a time when songs were expected to tell stories, and the songwriters who were masters of storytelling were sought after as aggressively as any first-round quarterback.

Tempchin’s tunes have taken root in so many minds, and have lifted so many hearts in the decades since he wrote “Peaceful Easy Feeling,” and “Already Gone” for the Eagles. The prolific songwriter’s music continues to fill arenas and sell millions and millions of albums for others. It’s been all about the songs, not the man. Despite the fact that Tempchin performed his music to audiences around the world for years, and despite the fact that he’d written hits for (or with) musical luminaries like Emmylou Harris, Glen Campbell, Tanya Tucker, Tom Rush, George Jones, and Tom Waits, the limelight has always been elusive for Tempchin—as have record deals.

That all changed when he was approached by Blue Élan Records who offered him his first contract since Clive Davis’ Arista Records in the late ’70s. That sparked something in Tempchin, and a backlog of songs came pouring out. “I was so excited that somebody was going to care whether I recorded something or not,” Tempchin tells TVD in our chat with him. So many songs were unearthed and so many more were inspired by this label’s confidence that his two-record deal turned into a three-record deal, with no signs of stopping.

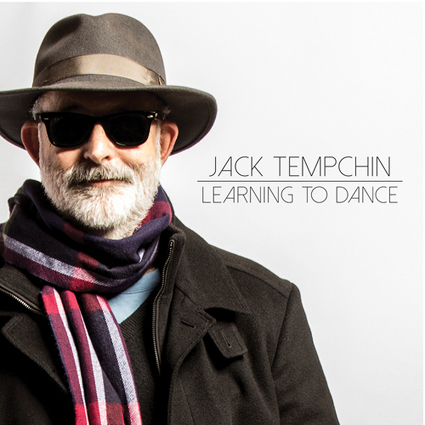

Tempchin released an EP, Room to Run, in May to tease his creative “explosion.” He followed it up with a thematic and poignant LP (released on Friday), Learning to Dance, which is his first album of new studio recordings in over eight years. His enthusiasm is massive when it comes to songwriting, as evidenced both in the lovely new album and through his songwriting “inspiration campaign” at GoWriteOne.com.

“It’s impossible to overrate the importance of songs,” he says. There’s absolutely no argument from us.

When you performed at The Troubadour in May, was that the first time you’d played all this new music live?

Yes! I hadn’t done any of those songs, and it was the first time I’d performed without playing guitar, too. [Laughs] This album was produced so differently, that I didn’t think about having to do the stuff live until I finished the album. And it turns out I couldn’t—I needed a whole band to pull it off. I rehearsed for quite a while with those guys because it was a first for me, standing up there and playing without doing my guitar.

Of course the second half of the show, I was doing my hits—stuff I had done before. Being back at The Troubadour and having all those people there… it was great to be there again.

When was the last time you’d played there?

Oh, let’s see… it was about five or six years ago when Timothy B. Schmit had a solo album that he was promoting, and I opened the show for him, just by myself at The Troubadour, and that was pretty great.

Hey, I noticed you interviewed Paul Williams. That’s pretty cool.

It was! He was such a fun person to talk to.

You know, I’ve known Paul for… we wrote a song together many, many years ago and we’re still workin’ on it. [Laughs] Man, he’s done so well. He’s so cool. That was a good article—thank you!

Thank you for saying that. You’re both highly respected, wonderful songwriters who were always sort of “behind the scenes.” But that has led people to constantly “discover” you over the years as they realize the people who wrote their favorite songs are not the people they thought! Is that strange to you? Or is that something that motivates you creatively?

I mean, it’s fantastic to have something you’ve done that people can hang onto and go, “Oh! That’s who that guy is!” and also say, “What an interesting thing you’re doing now!” It’s super great.

What’s so cool, too, is that you’ve had this kind of resurgence in songwriting lately. Learning to Dance has this big, open feel to it. I get that it’s this journey, but with music and your lyrics, it sounds like the soundtrack to a film and a screenplay. Is that something you had in your head as you were writing all this music?

Absolutely. Absolutely! It’s all cinematic. I like imagery. I like to put imagery into the songs. And then when the songs started coming together, I looked at them and thought, “This is a history of love.” It starts when love is euphoric, then the part when you realize there’s gonna be some problems, breaking up, getting back together… I just saw the songs being that, so I started stringing them together in that way.

When you were signed to your new label to create this album, was that what you had in mind?

No, you see my brain exploded! I was so excited that somebody was going to care whether I recorded something or not, I went through every song I had ever written, and I tried to pick the songs that no one had ever heard that I still thought were good, pull them out and record them—or maybe finish them and record them… that was just a big process.

But then once I started recording them… I picked Joel Piper, who is twenty-nine years old—he played drums for me at The Troubadour—he’s an amazing producer. Somehow, his musical experience at twenty-nine is completely different from mine. At some point—he’d been doing all of his techno stuff—we talked and we realized that if we worked together that we’d create something that nobody else is really doing.

So, as the songs started to take shape and I could hear how they were sounding, I wanted to put together an album with a package of songs that you can go through as an experience, and trying to do it with songs I’d already written, but that nobody had ever heard before!

Over how many years did these songs span?

Well, “What If We Should Fall In Love Again?” was written a year ago; there were a couple that were written quite a long time ago. “Learning to Dance” was written maybe ten or twelve years ago with my co-writer John Brannen, but there were a couple of songs that were brand new. So, yeah, it spans a lot of time, but I thought, no one but me has ever heard these songs, so it doesn’t matter if I wrote them a long time ago. It’s just for me to bring them together so they sound right and make sense.

I have to ask… if your “brain exploded,” are there more songs in the wings?

Yes! Once I turned this in, I asked the label and they said, “Go ahead and start record two,” because I had a two-record deal. I’m finishing up “record two,” for which I have twenty-something songs. And then they okayed a third record, and I’m kind of halfway through that as well.

So, when I say my brain exploded, I’m recording thirty or forty songs, and writing a whole bunch more. It’s just exactly what I want to do and where I want to be.

That’s extremely impressive for any songwriter, but especially for someone like you, who could rest on his laurels more than most…

I certainly could. I’m quite experienced at it; I’m quite good at doing nothing, but this is a lot more fun. [Laughs]

You mentioned your producer, Joel Piper, a bit ago. How involved have you been in the arrangements of these songs, and how much has Joel been involved?

A lot of the work has been his. I mean, I give him the song in the first place so he has a sense of it. Then… well, he plays almost all the instruments. He and I did the whole thing—there are only one or two other people involved on a few things.

What struck me from the beginning is that he’ll take the song somewhere that I wouldn’t take it, but it’s still… he keeps the center of the song and makes it better. He helps the song communicate itself more.

But most people who can manipulate the music and do all that, that’s a thing that they can’t do. They can make your record sound any way you want it, but they can’t find the heart of the song and keep that in the front like he does. I have tremendous respect for his production abilities. It’s a thrill working with the guy, and I just want to keep doing it.

To find such a great partner like that to make sure the songs produced stay true to what you intended them to be and make them even better is huge.

Yes, it is. So, to find a record label that believes in me and a producer that really works with me is just two amazing things that I didn’t expect to have happen, and I just couldn’t be happier about it. It’s so cool.

I love that you continue to be so creative and write your songs. People always connect with a well-written song. What I think is interesting is that while they may connect with the song, they don’t connect the song with what it actually takes to write a song. Do you feel like that’s the case? If you do, how has it affected you as a songwriter?

Oh, yeah. Over the years, I look at the music and I see that there are all different kinds of music. And there’s music you listen to for the song, but then there’s always dance music at all times throughout history—whether it’s hip hop or disco or whatever—that doesn’t have the same heaviness of lyric a lot of times, because it doesn’t need it and it’s not appropriate. That’s not what that music is about. So, there’s always that back and forth.

I enjoy both things, but I like to have a song that reaches in and gets you and moves you, and you can’t get it out of your head because a person is saying something. But that stuff moves in and out of fashion. A lot of the records now, they’re not really designed for that somehow. Some people are missing that.

I think it’s there, and people want it if they can find it. It’s like how the pendulum has swung back from reality TV to story- and character-driven shows being the most popular thing on right now.

I think also this has to do with technology. It’s not one big market anymore. The internet is fragmented into lots of smaller markets. I think there are a lot of people, both young and old, that are exploring songs written by songwriters… they can go back in time, they can listen to the stuff now; people who like a certain thing can pursue that thing and get it. We didn’t have that option before.

And so, I think it’s a glorious time for music, but as far as the commercial stuff—big money radio—that will be curated by commercial forces. Sometimes you get lucky and something great gets on there by mistake.

Adele might be a good example of that.

Yeah! Because people heard her and said, “Oh my gosh! That’s something real!” [Laughs]

Given that everything can be playlisted and there’s such a focus on singles, do you feel that the album as a format will survive?

That’s a good question. I think it will survive. Although, you know, the format is always changing with technology. With CDs you could only put a certain amount on each side, and so that’s what they did. The format decided how long a song was.

I don’t know what’s going to happen. I think people will preserve the album format. I think they’ll look at past things and say, “Oh, this is an album!” and they’ll understand that experience. But all I know is the interest in music is stronger than ever. As, worldwide, more and more people have access to music, they’re going to decide whether they want albums, what kind of music they want to listen to, and they’re going to steer the path more and more because they’re not dependent on Clear Channel. Now everybody can have their own radio station! But I don’t know what will happen to the “groups of songs” that become an album. I guess that’s my answer: I don’t know. [Laughs]

Okay, that was something I was especially curious to hear form you, especially since Learning to Dance is so clearly meant to be listened to as an entire piece and as an experience.

Well, I sure love having that format and being able to make music like that. Whether people want it or not… they can just pick the ones they like best on iTunes, but it would be nice if that format would survive.

Did that factor into your decision to release Learning to Drive on vinyl?

Yeah. I was just blown away seeing that vinyl! It does make a statement that this is a collection of songs that was done on purpose like this. I’ve got to say, I used to have vinyl of course, but I don’t have it anymore like everybody else. But man, I just love that record. I love looking at it… I love vinyl.

My friend Carrey Ott, who wrote “Room to Run” with me, one night we just sat around listening to his vinyl collection and it’s just, like, so different. The whole experience is just so different. I’m still in love with it! But the other thing is that… I don’t have an old ’57 Chevy, even though I love it. [Laughs] It doesn’t mean I love it any less, though!

Where you do stand on the sound quality debate when it comes to streaming music? As long as more people have access to music, do you feel that it’s that important?

It is important. We changed over the MP3 and these formats that don’t have the resolution and nobody cared because they were so easy to deal with. I think the technology will allow [better quality], like with Neil Young’s thing, next time there’s a bigger jump in bandwidth and computer power.

But I’ve always been able to listen to a song on a transistor radio, like when I was a kid, and still love it. I appreciate high sound quality, especially making records, but I can still enjoy a song even on tiny little headphones. Either way.

It’s all about the song.

Yeah, pretty much for me. It reaches you either way, so…

Do you feel like you’ve become a better artist over the years?

Well, let’s see. Within all reasonable parameters, I think I have become a better artist. I sing better, I play better. However, there’s a questionable thing for me: have I written a better song than “Peaceful Easy Feeling”? You know? [Laughs] Have I done a better concert than when I opened for Jackson Browne in 1973? Gee, I don’t know. I think as an artist you think you’re improving. As a writer, like you are, you think “Well, I’m a lot better than I used to be,” until you go back and look at your stuff and then you go, “Well, I’m better in a way!”

Does art really get “better”? We work on it night and day, every musician I know, for years and think we must be getting better. But sometimes you see a video from twenty years ago and think, “I was already pretty good!”

I’ve done everything I could to be better, and maybe you have to keep getting better just to stay afloat. But I don’t ever think that I “peaked” or anything like that. I always think I do better than I’m doing.

I am truly still 1,000% in it. That’s what I can say!

Jack Tempchin’s Learning To Dance is in stores now via Blue Élan Records. On vinyl.

Jack Tempchin Official | Facebook | Twitter

PHOTO: JOEL PIPER