Henry Diltz is making tea in his North Hollywood studio. His mid-century digs are filled with stacks of photography books and boxes of negatives, vinyl records, and box sets. One wall is filled with neatly labeled little drawers, each filled with hundreds of slides. Each drawer has a label like “Tom Waits” or “The Eagles” or “Neil Young.” It’s a photographic card catalog of rock and roll.

Henry Diltz got his start as a photographer serendipitously; he would say it was the result of many “happy accidents.” As a member of the Modern Folk Quartet during the folk revival of the late ‘50s, Diltz toured the country with the group and played the same clubs as Joni Mitchell, Stephen Stills, John Sebastian, and many, many other early rock ‘n’ roll luminaries. A random purchase of a thrift store camera—and one scrapped Phil Spector-produced record later—and Diltz found himself taking photos of his musician friends instead of sharing stages with them. That drastic change of career trajectory never phased Diltz; the guy is impossible to discourage.

The tea is ready, and he smiles excitedly as he sets the cup down. When I arrived, he was going through a proof of an Australian magazine that’s publishing several of his photos:

“Here’s Keith [Richards] and Ron [Wood] on a Lear jet… Here’s The Doors at the Hard Rock Café in downtown LA. Tom Waits… two Neil Young shots…” He’s about as nonchalant as someone who has a digital Rolodex of legendary rock stars can be.

“There’s Michael Jackson… then Kurt Cobain from Nirvana, then Stephen Stills and Mick Jagger in Amsterdam…”

Times may have changed, but Diltz’ photos remain an archive not just of rock royalty, but an archive of the man’s sense of fun and his pure enjoyment of life. While his iconic works can be found at the Morrison Hotel Gallery (of which Diltz is part-owner), he remains active and still shoots album covers and portraits. But most of his photography now is focused on his artistic whims, like photographing series of things like hearts he finds out in the world, or fire hydrants, or beautiful tattoos.

Our candid chat covers a wide swath of his career, his early experiences, and his cheery outlook on life. It’s hard to know where to begin and end with Henry, as he’s the kind of artist who makes everything memorable.

I have to settle a bet before we start. I bet a friend that you were the one who played banjo at the end of “Bluebird.” He said you didn’t.

[Laughs] He’s right, I didn’t I played banjo on “Elusive Butterfly” by Bob Lind. [Sings a bit of it] It was a hit in the ‘60s; and “Don’t Cross the River” by America. You can hear me tinkling away in the background.

No kidding! That’s how you had an “in” with these guys, because you were a musician like they were, not just some photographer.

Yes, right!

You have photographed some of the most iconic album covers. One that’s always stuck with me was the Crosby, Stills & Nash album cover. It feels like it was always around in my house—like a picture of some distant uncles. When you were taking these photos, did you set out to make a memorable artistic statements, or were you just having fun with your friends?

No, it was more just a fun thing that we did every day. That particular cover… well, first of all, I knew those guys. I knew Stephen way before Buffalo Springfield when I was a folk singer in New York, and he would come to a club to see us [the Modern Folk Quartet]. I met Graham in The Hollies, and I knew David before The Byrds, just hanging around the Troubadour club in probably ’63… ’64? They were very good friends of mine, and when they got together as the famous CSN, everybody was very excited. I went down to watch them record and they needed some kind of photo to show that they were together. They weren’t talking about an album cover; they were recording, but they just needed a publicity photo—something to announce that they were recording together.

I had a partner, Gary Burden, as a graphic artist. I would take the pictures and he would lay them out. We worked as a team, and we both knew CSN very well. One day he called me and said, “We’re gonna drive around today with those guys and take some publicity photos.” We started in Gary’s garage and took some portraits, then we got in the car and drove around. Graham had seen this little, old, funky house with a couch outside. We stopped there, they got on the couch, and we took some pictures. Then we went down the street and around the corner to a clothing store and took pictures outside of that, and they tried on some different things… it was just a day of having a little adventure, driving around west LA, stopping here and there and taking pictures.

So, that house and that couch was not a big plan—it was just a little stop along the way. I took transparencies and then we’d have a slide show. When we looked at that, everybody said, “Wow! That’s a great shot!” But between taking that picture and looking at them, the day or two in between, they finally settled on the name: Crosby, Stills and Nash. Stills, who was kind of the main musician and leader of that group—especially the first album, he was really responsible for it and played most of the instruments—he kind of wanted to call it Stills, Nash and Crosby. There was a discussion and they eventually settled, of course, on Crosby, Stills and Nash. So, they thought this photo was a great cover, but the names were backwards—it’s Nash, Stills and Crosby. I’ve told this story so many times… [Laughs] I just said, well, let’s go back there and re-take the photo. We got in the car and got there, but the house was gone! So, we had to use the cover with them being backwards.

You know, in those days I was having so much fun taking pictures. I just loved to do it. It was something that came really naturally to me. I like looking at life that way. I like squaring things off, framing. I had a framing jones. I like to frame things. I do it with my eyes just sitting; if you open one eye, or the other eye… if I’m sitting at the window, I look through the panes of the window. If I’m looking at the house across the street, and close one eye the pane covers the front door. I play with that. I guess I’m a visual guy.

What I find really fascinating about you is the way you started out, as a musician… you were presented with a totally different artistic opportunity and you went with it. I don’t know many musicians would give up a record deal to be a photographer.

[Laughs] In college, I was studying psychology because I’m real interested in people and what makes them tick. I went to college for five years, and I never did graduate. But I took all the psychology courses, then philosophy courses and literature. I just loved college! I loved hearing the learned professors talk about their favorite subjects. I ended up at the University of Hawaii and I got into a coffee house there; I met a guy who had a coffee house called the Greensleeves Coffee House. It was around ’59 and folk music, like The Kingston Trio, was getting huge. I had a banjo and I ended up going down there every single night and I wound up playing, we worked up several groups, and then moved to LA to seek our fortune.

We played at the Troubadour in late ’62… the funny thing is we were a four-part harmony group. There’s not a lot a four-part harmony groups. Crosby, Stills and Nash are three… Peter, Paul and Mary… but four-part is way different than three-part, musically. Three-part you sing the melody, someone sings a third above, someone sings a third below. The fourth person you have to stick in there and make it a seventh or a ninth—you make a jazz chord out of it. It sounds way more full than three-part harmony.

So, we had sung together for a couple of years in Hawaii and perfected this. We sang every night at a crummy little steakhouse where sailors would have fights and stuff. We just sang these folk songs and had them down so well, that when we came to LA and played the Troubadour at a hootenanny night. We sang the first chord and the whole audience rose up clapping—it was astonishing! It was scary! We didn’t expect it. We were just singing our song, but we hit this chord and then… [imitates a crowd cheering]

So, we had sung together for a couple of years in Hawaii and perfected this. We sang every night at a crummy little steakhouse where sailors would have fights and stuff. We just sang these folk songs and had them down so well, that when we came to LA and played the Troubadour at a hootenanny night. We sang the first chord and the whole audience rose up clapping—it was astonishing! It was scary! We didn’t expect it. We were just singing our song, but we hit this chord and then… [imitates a crowd cheering]

We got a manager and a record company and an agent—right out of that first performance. That was pretty amazing.

I always had a kind of a knack for lettering and handwriting. My stepfather was in the State Department, so I grew up in Tokyo and Thailand and Germany. And I would write postcards to my friends, and I would print and realized that when I was printing, if I would just connect the letters together it would be quicker—sort of like calligraphy. I figured out my own form of calligraphy. So, I did have that sort of artistic feeling, you know? Laying dormant in there was this visual thing.

I remember in the group at one point… well, let me just say that smoking God’s herb has definitely almost everything to do with the fact that I became a photographer. We’d be on the road in a van—one trip we took a camper cross-country for three months, just doing folk clubs, colleges, TV shows… And we would smoke a little just to make the day open up and put a cool edge on everything. It just made things more interesting. You got into things and you got more ideas. You felt more happy and got more excited about everything, right? So, we just did that.

On that trip at one point I remember in New York City I had a color breakthrough where I suddenly started seeing colors in a new way, and I got a pad and paper—I had a sketch pad and oil pastel crayons, like a hundred different colors—and I would see things in the van as we were driving. I remember in the South I saw a black lady and a little boy walking down the side of the street and the colors they were wearing… the tops and bottoms, I had to grab the pencils and get just the exact colors and just quickly sketch that—just to remember that color combination! It’s like I rediscovered colors! It might have come from taking psychedelics, too. I took a little of those—not a lot. I wasn’t one of those people who took those every day. I probably took psychedelics a dozen times in my whole life. Maybe once a year or something.

Just to kind of open the third eye or something…

Yeah! So, I had this color breakthrough. We learn our colors in kindergarten, but I never really thought about it since then! I can’t explain it. I’d lived all over the world up to that point and always enjoyed the sights and sounds and all. But this suddenly was just knocking me out. So then on this last tour we took in this camper, cross-country in ’66, when we were coming back home we stopped in a little second-hand store in East Lansing, Michigan. We went in just to spend a little money on stuff we didn’t need. There was a table with little used cameras on it, and we all said, “Hey, what the hell?” Then one of the guys, my friend Cyrus, bought each of us a roll of Kodak film. I said, “How do you set these numbers on here?” And he said, “Well, just look on the box and it says, ‘Sunlight – 250 at 8’.” We stopped the van for a field of cows or a junkyard… we’d just stop all the time and we’d jump out and take pictures of each other or whatever was going on.

When we got back to LA, I developed the film and only then realized it was transparencies—slide film! He would’ve handed me black and white, and I wouldn’t have known the difference then. We got it all developed and decided, “Let’s have a slide show!” So we all got together to look at our slides. All of our friends were there, and we had a little smoke… it was the ‘60s and we were all hippies, so that’s what we did all the time!

People were just blown away by the slideshow, including me! The first slide just hit the wall, shimmering and, just… WOW! Slides are lit up in a way… and it’s not the same with a digital slideshow. It’s that piece of plastic with the light shining through it… it just blew my mind. I couldn’t believe how magic it was. People seemed to really like my pictures, you know, because I was really careful about framing and moving in and getting it just the way it had the most impact for me. I want to get the essence of the scene—just the part I want. I can frame it in the camera the way I want. And so, always, I never cropped pictures; I did that when I took the picture. I never printed them, either, and I’d show them in a slideshow, so you can’t really crop them to show them. So, it had to be just the way I wanted it to be. I didn’t have any tricks, I just wanted—if I was looking at an old truck, I wanted to get the essence of that old truck. I would frame it very carefully, get just the right angle, take a very careful light reading… and I just wanted it to look exactly like that. I wanted to get the essence of that old truck in a photo that just said what it was that moved me about it. I was that way with people, too.

When that first slide hit that wall, I said “ I’ve got to take more of these so we can have more slideshows.” That’s when I started photographing during the week, and photographing my friends. I would do it all the time. I hung out with these people all week; they were my fellow musicians and their wives and girlfriends—our karmic group. I would love it when I showed up with my pictures and they’d say, “Oh, wow! I didn’t know you took that picture of me!” That’s what I liked to hear. They were candid shots of these people I loved, but I was on a mission to surprised them with all the pictures I could take of them. That became so much fun! I’d get the little yellow box back from Kodak, sit at my slide board late at night, have a little toke, lay the slides out, and look at them all… label and number them.

When I took so many pictures of my friends, there would always be a few where they would be reading or sleeping or taking a nap or eating. After a while, I noticed they were starting to fall into categories, and so in a way of editing them and showing them—because you need a flow, I wouldn’t just throw them all in a tray—I would start with some really colorful things and end up with funny things—I had an idea of the flow.

I would do these series and then when I really became a photographer and started traveling around the country… the first tour I ever did was the Lovin’ Spoonful in ’66. As we went on a little plane around the Midwest, every little town we were in I would notice, because I was so attuned to colors, that the fire hydrants were different colors—in every town! We think of them as all red, traditionally. In LA, they’re all yellow. In San Francisco, they’re white and light blue on top. In New York, they’re black and silver, but there’s every combination all the way through. And so, on that tour, I photographed many, many fire hydrants! That was my first real series of things.

Over the years, I’ve taken thousands of photos in all different categories. I’m a Virgo, so we like to compartmentalize things and put things in boxes and analyze—I think it’s a kind of Virgo trait to collect these things. Stars—I have hundreds of stars! Hearts, tattoos, graffiti, people giving the peace sign—like this [gives the peace sign], people giving the finger—lots of those, especially David Crosby. [Laughs] Trucks, barns, flowers, animals, people with animals… just so many things. I would do this for my slideshows: “Oh, the toilet series!” This became fun for my audience of friends.

It’s kind of a hunting thing. I was reading a book recently from the Laguna Beach library of photo essays by people like Walker Evans and Paul Strand—some of those guys back in the ’40s. Walker Evans was talking to a class and he said, “My eyes collect things. I’m a collector with my eyes.” At one point he even said, “My eyes are hungry.” And I thought, that says it! I’m a collector, too—I just collect images of things.

It sounds like the origin of that “collecting” came from your childhood, growing up around the world. I imagine that must have been very lonely for you at times.

Well, that helped me with people. As a young kid going to school with Army brats, you would be the new guy, make best friends and they’d move away, or you’d move away. It was always a big flux of people coming and going. So, I had many different sets of best friends in various eras of my life, in the various places I lived. I can’t remember being turned on visually in any of that, really. I mean, loved music. I played the harmonica in the Boy Scouts, and played the clarinet in Thailand, and I sang in glee clubs and choirs all over the place. I knew I loved music, but I never really got into any kind of visual thing. Heck, I saw an awful lot of stuff. We had a big field of water buffalo across from our house in Thailand! But I never thought of taking a picture of it, or draw it or anything. It was just fun to look at.

I’m pretty sure it was smoking grass and psychedelics—LSD or psilocybin or mescaline—they can be a huge teacher, and open up your whole life. Jerry Garcia had this great quote: “The first time I took acid, I said to myself, ‘I knew there was more happening than they’re telling us!’” [Laughs] I mean, you just see life as much deeper and with much more meaning… you don’t take life for granted after LSD, if you do it the right way, the way Timothy Leary taught—in a great place with friends, uninterrupted, and let it work on you as you meditate.

I watched a lecture with Timothy Leary where he said that acid “interrupts your imprinting,” and “imprinting” means… [points around the room] that’s a stove, that’s a teakettle, that’s a phone—we know all that stuff. We take all that for granted. When we see a car, we don’t think, “Wow, what’s that metal box with those rubber round things going down the road?” When I first took acid, I remember looking down at my hands and thinking, “My god! I can’t believe these are mine! These are great! It’s a part of me!” You discover life anew.

We’re getting a little far afield, here… [Laughs]

So, you were doing all these slideshows and taking photos of your musician friends. Meanwhile, what was going on with your own musical career with the Modern Folk Quartet?

We recorded a single with Phil Spector and we thought that was it. In fact, Brian Wilson came down to the control room in his robe and slippers and listened to our record over and over and over again, because we were a four-part harmony group, and that was Brian Wilson’s stuff. It was more up his alley, and he revered Phil Spector. Brian was a god to us. We didn’t even talk to him, but we saw him in there listening to our record twenty times and we thought we’d gotten the break for our career.

But Phil wouldn’t put it out! He was very paranoid in those days, and we were a folk-rock experiment for him and if he wasn’t sure it would be number one, he wouldn’t put it out. So, he just sat on it for the longest period of time. We took that last tour and one of the guys said, “I’m going back to Hawaii. Call me if anything happens.” One guy joined The Turtles and produced The Monkees—that was Chip Douglas. And then Jerry Yester arranged for The Association—his brother sings for The Association. Cyrus [Faryar] went back to Hawaii and produced stuff there. We all pursued our careers. I had the camera then, so we just kind of quit—set it down. I was off taking pictures of all of my friends, who were up in Laurel Canyon. They were people like Mama Cass—especially Mama Cass—but also Stephen Stills, David Crosby, Joni Mitchell… all those people. But I was just Henry with the camera; I wasn’t perceived and anyone “outside.”

And that comes through in the natural, candid nature of those Laurel Canyon photos…

They didn’t notice me as a photographer.

Right.

I was just doin’ what I did. It wasn’t so much that I’d be hired… I didn’t go to photo school, I didn’t know lighting, I didn’t shoot in the studio—I didn’t know any of that. It was a while before I got hired, so I was just shooting all my friends and the things I saw.

Did you ever feel intimidated by established professional photographers?

No, and I didn’t even see any other photographers. It was just my new-found passion. After I took those random photos on the road and saw what those slides looked like on the wall, that was it. I just wanted more. A few years later in ’69 when I started doing album covers—mostly with Gary Burden—I got a call one day from Peter Asher who wanted me to come over and take pictures of this guy named James Taylor. He told me he needed some publicity photos for him. Back then, “publicity photos” meant black and white because they couldn’t put color in newspapers.

So, I went over to Peter Asher’s house and there was James Taylor, sitting on the floor playing his guitar. He was fingerpicking “Oh, Susanna” like a music box, as only he could do it. I was just… I fell down to my knees in front of him just awestruck—just gobsmacked by this picking and playing he was doing, because he’s the greatest in the world at that! I couldn’t believe it. I asked him if he could play it one more time. He was very quiet and very shy, but he did and I took a few pictures.

Then I said, “We need to go outside somewhere where there’s good light. Let’s go to my friend Cyrus’ house.” We called his place “The Farm” which had a couple of houses and some barns and sheds. James and I walked off by some of the old sheds, and we took some pictures there. There was a big post sticking up and he just came over and rested his arms over the post. I framed it up and it just filled the rectangle perfectly. I took a couple of black-and-whites, but I thought, “ I’ve got to get a color shot of this to show in my slideshow!” I got my other camera out to take a few shots for me, of this blue shirt and this sort of reddish barn behind him. That’s what ended up as the album cover. But that’s how I was thinking in those days—I’ll shoot black and white for you, but color for me because I need color for the slideshows.

When you started shooting album covers, did it change the way you thought about your subjects? It wasn’t always your friends anymore.

I always say that I like to document, like a fly on the wall. I don’t like to tell people what to do. But of course, you’ve got to direct people! But like that CSN photo, I didn’t tell them where to sit. Graham sat on the back, Stephen sat with his guitar, and David just kind of plunked down. We didn’t change it—it was just the way it was. When we did The Doors’ Morrison Hotel, they just ran behind that window and got in there, and that’s the way it was. I just pulled the trigger! [Laughs]

Gary and I perfected this way of doing album covers where we’d try to have a little adventure, so that the group would have some fun. We’d try to get out of town so they’d be away from their girlfriends and managers—to get their attention. We got in with Elliot Roberts, who managed Joni Mitchell and Neil Young, and then David Geffen became friendly with us. We started doing all their photography and all their album covers. They got The Eagles and they needed an album cover, so Gary got the idea that we’d go out to the desert—Joshua Tree—go out there and spend the night. We had no real plan, so we’d just go out to places like that and he’d say, “Just shoot everything! Film’s the cheapest part!” [Laughs] The other thing he’d say was, “Back up! Back up!” When CSN were on the couch, I was framing it tightly with the couch because it fit perfectly. But Gary said, “No, back up, back up and get the whole house!” So I backed up across the street and go the whole house.

Same with The Doors’ Morrison Hotel. They got behind the window and I started up close, sort of from the side and looking down. But Gary again said, “No, back up and get the whole window straight on!” We worked together really well, even though we wouldn’t plan what the image would be, it always would present itself. I used to worry about that in the old days, but now I never worry about it. I’ll come over, we’ll find a place, I’ll take pictures, and it always works out.

The way that photography relates to album covers, and the whole aesthetic of having and holding an album… there’s this complementary experience. But it’s an experience that’s often regarded as unimportant or redundant these days.

It’s an art form that has sort of disappeared. That was such a huge part of the music experience. You’d get the album and it would have a huge picture on it. You put the album on and sit there and look at the picture and read the liner notes. People tell me all the time, “I don’t know how many hours I stared at that album cover!”

You got your whole image of the group by the album cover. It’s not the same looking at little pictures in a CD booklet; it’s like looking at a tiny magazine instead of that great, big, beautiful album cover. A lot of thought went into those. Gary Burden, my partner and art director, was so good at picking the best picture and putting the lettering in just the right way to complement it. He was a guy with a great artistic sense of what was really gonna live.

Honestly, now, what do you think of this vinyl revival going on?

It’s great! I went into a new record store off Cahuenga the other day, and it’s full of thousands of pieces of vinyl. It’s fun to look through them. I [recently] took a picture of a young Americana group called The Dwells for their vinyl record.

That’s a great photo. The image made such an impression on me that I sought them out.

Yeah, because it had an impact seeing a picture that big. That’s why, I guess, groups are getting back into it. They always have a few hundred pressed. Maybe it’ll come back… I don’t know. Now, it’s all on the internet—CDs are passé now, or getting there.

How did things change for you after the ’60s and ’70s?

Well, the ‘80s was the decade of videos. Everybody was shooting videos, and I would be the still photographer. Sometimes there’d be two or three shoots a week. Sometimes they’d last all night! I loved it! When you would get hired by a record company or a production company, they only wanted one shot: they wanted the director or the star, and they wanted to see the camera in front of them so that the publicity shot could be used to announce that they were doing a video. Some of these guys that did what I did would go and they would go by several sets a day, wait a half an hour or whatever, take a roll of film of the star and director and be off. That’s all the record company really wanted—they only paid them for that. But I would stay eight hours, ten hours—I loved it! You could hang out with the people there and the music was playing, and there were young interns and the film crew, and people! I just love interacting with people. Plus, I could shoot—it was all well-lit, and whoever the artist was would be all dressed up, and you could click away while the music was playing. I did tons of stills on videos.

I knew that getting that one shot for Billboard was one thing, but if I stayed and got that star really at a great moment singing, very often that would get used for something like a single sleeve or an ad or a poster or whatever. Because the record company didn’t want that stuff, I kind of kept all that. So, I’m kind of lucky that I have a huge archive of photos. Many photographers who worked for record companies don’t have their photos; they have the rights to their photos, but most of the record companies lost them all or stored them away. There’s been a couple of photographers who have sued to record companies to get their pictures back.

But I was able to hang onto a lot of mine, and also because Gary and I did photography for the groups—we worked for the management, not for the record company. In fact, the record company wouldn’t like us because they have their own art director and their own group of people. They wanted to do it themselves. But [David] Geffen and [Elliot] Roberts… it was an interesting confluence of events that happened, because Geffen was such an advocate for his musicians. He got them so much more power than they had before. When I was in my group, we’d walk into the studio and they’d hand us a record and say, “Here’s your album cover, boys!” We never saw any of the pictures or got to pick or do anything. And that was always the way it was. The record company would do your cover and lay it on ya. But Geffen made sure that all of his groups had the artistic rights to do their own artwork, and to have the final say on everything.

David Geffen was really a formidable presence, wasn’t he?

Oh, yeah. He was a wheeler-dealer. I would hear him on the phone in his office—I would go by there almost every day because Graham Nash would be there or David Crosby or The Eagles or Joni Mitchell—there’d be all kinds of people hanging out in their suite of offices on Sunset. Gary and I would be running around doing errands, or I would be going to the photo lab, and we’d stop in to use the phone or say hello to the secretaries, have a little smoke with whatever musician was in there. It was just a stop along the way! And I could hear Geffen down the hallway, shouting into the phone. He really was a force.

I met Elliot Roberts and spoke with him briefly and his presence is very much… you know who’s in charge.

They were the bulldogs; the keepers of the gates. It was great to be in on that, and that had a great deal to do with my career as a photographer, even.

Because you were in the inner circle with the artists.

Yeah. But interesting things happen along the lines. First, I started taking these pictures and became obsessed with framing and slideshows. And then, during the folk days, I was on a forty-day bus tour called a hootenanny tour. There was a bluegrass group called the Knob Lick Upper 10,000 from Oberlin College. I don’t know what it meant. So, the banjo player in that group was a 6’5” Norwegian kid named Erik Jacobsen. We became really good friends on that tour. A couple of years later, he was in New York and started to produce records. He called me up one day in ’66—right after I got my camera—and he said, “Henry, you want to learn to be a photographer in the music business? Come to New York for the summer. We’ll pay for all your expenses.” He told me The Lovin’ Spoonful needed a bunch of pictures for magazines and publicity and all kinds of stuff, as they’d just had a big hit with “Do You Believe in Magic?” That was the first tour I went on that summer. It was like an apprenticeship to be a rock photographer!

Then I flew back to LA, and on one of the first days I was back I was up in Laurel Canyon and my phone rang and it was the editor of Tiger Beat magazine. He asked if they could hire me for the day to go down to The Monkees TV set. It was the next real job I had. They wanted tons of pictures for covers and posters and anything they could get. My job was to shoot ten to twenty rolls of film and give it all to them, and they would pay me for the day. It was real good money, and it was so much fun!

The first day I got down there, I was kind of the same age group as The Monkees. I had longish hair and love beads—I was a hippie, and they were, too. Before me, they had all these square old guys—these AP photographers who would say stuff like, “Okay, boys, do something zany!” That was the stuff they hated! I didn’t do any of that—I just sat there and took photos while they were doing all their stuff. And I just loved doing that. We became such good friends. This was the day when everybody was smoking grass. Mike Nesmith didn’t but he was one of the only people I knew who didn’t.

Years later when I started my gallery, it was all my photos at first. One day I was standing in there, and people were walking in and saying things like, “Wow! This was my whole life.” It was all the Laurel Canyon stuff, and we’d have tapes playing of Jackson Brown and Joni Mitchell and James Taylor and people would just love it. And so one day, someone asked me if I smoked grass with any of these people. I looked around the room and said, “I got high with every single person in every one of these pictures!” [Laughs] Except for Mike Nesmith and Donny Osmond. I don’t think I smoked with Michael Jackson, either, but all the Laurel Canyon people—all the folk musicians. It was like brushing your teeth, having a toke. Everybody did it. There was a point I was going to make… [Laughs] Oh! The Monkees set!

Micky and I had this routine where we’d climb this ladder on the soundstage, way up about three stories up into the rafters where they had the lights hanging. There were catwalks up there. We’d go up there and have a little smoke, and look around at all the people running around. Then we’d come down and Davy Jones would say, “Hey, man! Come into my dressing room— I’ve got a little something to smoke!” Then Peter Tork would say, “Hey, Henry, I’ve got a little piece of hash! And we could get a safety pin from wardrobe…” [Laughs] I would get stoned three times!

I think smoking grass… it enhances your senses. Obviously—it’s why musicians get into it. It made me take a million pictures—but good ones! It’s not like they were all crap!

You’re no slouch, Henry.

[Laughs] As long as you can get it focused right! I would crouch amid the light stands, because you didn’t want to ever get in the way, so I knew if I sat in the little forest of light stands, they’d never see that. I’d have a telephoto lens and I’d train it on one guy’s face and when he’d laugh or do something funny… I’d wait for that natural moment when they’d just look… lovable!

Same at a concert. Say Neil Young is playing. I’ll crouch there below the stage in the front and just sit there with my camera trained on him from the waist up, frame him so I’ve got the guitar, I’ve got him, and then when he does just the right thing… bang! I’ll get it.

Being a musician, too, I learned in the recording studio to click on the beat so I wouldn’t ruin the track.

Like those snipers who are trained to pull the trigger between heartbeats…

[Laughs] Yeah! Yeah! Someone like Neil Young doesn’t want to hear the click, so I could only take the picture at the right time. You don’t want to wait and do it at the wrong time and ruin his concentration. And, I always want to be unseen. I don’t want to interrupt anything. There’s a little bit of Jane Goodall in what I do. She’d sit there and look at the chimps and not want to interact in any way, or she would change the natural behaviors. Same with me. I wanted to photograph them in their element, doing what they did, not directing them to put a wastebasket on their heads or to jump in a tub full of milk.

Those photographers that do that are great at what they do. The covers of Rolling Stone are always quite thought out and fabricated and very interesting. But always in a studio and always with flash lights. It’s an art form—it’s just not the art form that I do.

Your in-the-moment album covers work perfectly with an analog format like vinyl. For a lot of people, it’s hard to justify having vinyl at all. You play it a few times and it starts to not sound so great, whereas you could have every song available instantly in perfect digital quality. Which is great! But I feel like maybe the way we consume music and the way that we consume art is removed from that human element more and more.

I mean, it started out with guitars and things. When I was growing up, there were blues singers, then these folk singers. And then Dylan and The Beatles just sort of happened, and all the folk groups saw that. We [Modern Folk Quartet] stopped and got a motel room because we’d heard of The Beatles, but nobody’d ever seen them. We sat there and watched them and we just couldn’t believe it. We said, “What are we doing playing a stand-up bass?! We need to get an electric bass, we need to electrify, we need to have some fun like they are!” And they started writing their own songs, and Dylan started writing his own songs.

I think what sums that change up really well in the music industry is an interview I heard with Jackson Browne. He said, “The first time I saw Dylan I thought, ‘Oh, I get it! It’s kind of a pop song, but it’s personal!’” And that’s it! It used to be songwriters and singers. Frank Sinatra never wrote any songs. Ella Fitzgerald never wrote any songs. Elvis never wrote any songs.

It all seems to come back around. You had all these people interpreting songs written by committee, then you had the artists themselves writing songs, and now it’s come back around to how it was—singles and songwriting committees.

The record companies got really huge, too, creating stars out of people who probably didn’t really deserve to be stars.

Which still happens now…

Right! But now it’s coming around again—it’s kids making their own music, recording in their garage or bedroom. It’s just that one song, five million hits, and suddenly it’s… wow! It’s crazy, isn’t it? It’s so different! Well, life trundles along and evolves in very interesting ways.

Back in the ‘60s when I started taking pictures, never once did I think ahead and think that I was capturing an era. In the meantime, I was amassing this unintentional history. It wasn’t until years later when somebody said to me, “Wow, you must have quite an archive.” And I thought, “Archive?!” [Laughs] People would also say to me, “Oh, you’re a photographer? Are you a professional?” And I’d say no. I raised my family and my kids and put them through school doing what I did, but I still didn’t think of myself as a professional photographer. That’s a guy who has a big studio and helpers and lights and books and photo sessions… It was just a thing that I sort of did because I love to do it, and it incidentally paid the bills!

The second inadvertent thing that came out of my photography is that I have a business selling the rights to these photos, this history of music. Every day, now. It started out that once a month I’d get a call. Then once a week. Then it was once a day. Now with email, I probably get three, four, five requests a day.

I’m glad I made it through the mire!

[Laughs] It’s magazines and it’s videos and it’s box sets… I waited long enough to where all these artists are doing “best ofs” and box sets of their whole life. I’ve got lots of pictures in David Crosby’s box set and Graham Nash’s and lots of pictures in Stephen Stills’. That group more than any—except for America—I photographed them throughout their whole lives.

When I was talking to Graham Nash, it was such an incredible thing for me, because that music has been with me my entire life. My mom would sing these songs when I was a baby. It was very profound in a way I wasn’t expecting. It kind of brought it all back home a little bit, why I do what I do. It was like looking at a piece of my life that I’d taken for granted.

Well, that’s no accident. He’s an amazing person. All these people that are famous in this music business, it’s no accident that they are because they are exceptional people. Joni Mitchell is amazing… Jackson Browne—what a guy he is! He’s the most fantastic, caring… he’s just such a great part of our fabric. Same with Jimmy Webb and The Rolling Stones and The Beatles. They’re just exceptional people and so talented and very driven and all those things—including lucky. But the cream does rise to the top, and they are amazing people. It’s been great fun—it still is fun—to hang out and watch these people. Like I said, I love observing people. Being a photographer is like having a passport into other people’s lives.

One day I got a call on my phone—all of these things started with a call on my phone in my kitchen in Laurel Canyon—and Rolling Stone called from New York.

“What are you doing today?”

“Nothing, sitting around.”

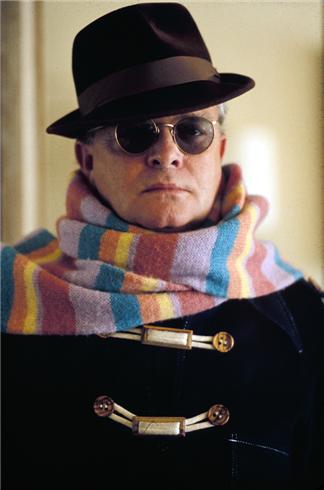

“Could you go right to Burbank airport, fly to Palm Springs, go to Truman Capote’s house? We have a story coming out and no cover.”

So, I went! I studied Truman’s short stories in college! And I just knocked on his door, and there he was! I spent a couple of hours with him, walking around his garden, talking, telling me stories. And I’m just taking pictures as we talk! I was about to leave when he said, “Wait! I have an idea.” He went back into his bedroom and came out with a big overcoat and a hat and a scarf around his neck. And he stood there in the doorway, and it was like 105 outside, and so I took a few last-minute color portraits of him and that became the cover of the Rolling Stone. Often it’s the last picture because you’ve warmed up for a few hours, the person relaxes more, and you’re working up to the final idea. That is the best example I have of being given a passport into somebody’s life.

I don’t shoot a lot of album covers now, but a few a year. Friends. Headshots I do. If people ask me, I’ll take a picture, but mostly I just photograph for myself. Just the stuff I like to see—I’m still collecting images.

Do you get tired of talking about the same stuff?

Nah! I don’t really know why. Every time I do a slide show today, I’m telling the same old stories to new people. I realize if I don’t tell it the same way, they’re not going to get it.

Would it surprise you to know that there are legions of young girls on Tumblr who share photos of these old bands? I’ve seen your photos there many times, especially among these gals who are big Lovin’ Spoonful fans.

Oh my God! Wow! I have a Google Alert set up to let me know when my photos get used. One time, there were a hundred pictures of Ringo and there was one of mine right in the middle of them! I thought it was great! I mean, I love for my pictures to be out in the world and be used. That’s the point!

What was the most memorable shoot that turned into a disaster?

There weren’t any real disasters. Gary and I shot a few album covers of bands who never really made it, but that’s about it. The worst is when you go to shoot a concert and the security will say, “No photos!” You’ll tell them that the band hired you to do this, but they keep telling you that there are no photos allowed. Over the years, I’ve had to deal with that many times—especially at festivals or big concerts.

How did the Morrison Hotel Gallery come to be?

Well, I met a guy who toured around with the John Lennon lithographs, and he’d go to different cities over many months where he’d sell these lithographs for Yoko—for the Lennon estate. And he said, “ I’ve been wanting to do this for something else, and I think your photos might work!” So this guy, Rich Horowitz, and I and my pal Peter Blachley, went around the country for a year. We’d rent a room in a hotel, find a gallery or a space somewhere that was empty, and just for four days we’d put all my pictures on the wall. We’d get in the newspapers, TV, radio—because they were small enough towns where we stopped. This was in the ‘90s. They would always talk about, “The Demise of the Album Cover!” and we’d get a full front page in the entertainment sections of these papers with photos and a big, long interview all about how record covers have disappeared. We’d do very, very well.

We ended up in New York and found a little place in SoHo and they wanted $35,000 a month to lease this little storefront. We said, “Look, we only want it for a weekend, so we’ll give you a couple of grand cash.” We had our show and we said, “Well, this place is empty—why don’t we try to keep it up for a few weeks for a month and pay the guy? He could still rent it or lease it, and it would look better with photos on the walls.” And that really worked! We were in the first place for a year. We didn’t sign a lease because we couldn’t afford it, and so we went to a second and a third place—three years doing that until we found our permanent gallery [in Greenwich Village]. Then we opened one up in La Jolla, and we had one on Sunset Boulevard. The one in New York, however, always does well because there are so many people who walk by and come in. Nobody walked by on Sunset Boulevard! [Laughs]

So, New York was going great and Peter suggested I contact another photographer and do a show, have a party, get some publicity. He asked me who I would like out of all the photographers, and I said “Jim Marshall!” He was my guru from San Francisco. He was kind of an irascible character, but he took great pictures. Then we added Bob Gruen, then we added Neal Preston who photographed Led Zeppelin a lot… and now we have ninety photographers including Pattie Boyd, Graham Nash, Joel Bernstein—on and on and on. If you look on our website, I think we may have more than ninety now. That’s another total surprise and inadvertent thing that has worked out interestingly, you know? [Laughs]

Now that those kids of the ‘60s and ‘70s are grown and are doctors and lawyers and whatnot, they have the money to say, “I want to remember that.” A friend of mine bought a picture of Jerry Garcia—he was a huge Grateful Dead fan. And he said, “You know, that’s over the mantle in my house. When I get home from work and open the door, that’s the first thing I see and it just makes me relax and feel good.” That’s sweet. I’m so glad I was accidentally able to capture some of these images that people remember. And I’m still taking pictures, too!

All photos (c) Henry Diltz. You can see more of his photos—and hundreds of photos from over 90 other music photographers—online at the Morrison Hotel Gallery or at their brick-and-mortar locations in New York City and Los Angeles.

HENRY DILTZ PHOTO: PAUL ZOLLO