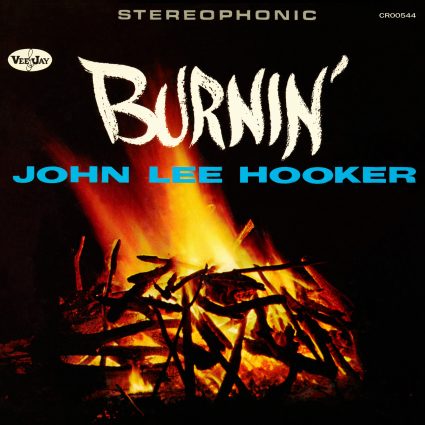

By the time John Lee Hooker recorded Burnin’ for the Vee Jay label in 1961, he’d been on the recording and performing scene in and beyond Detroit for roughly a dozen years, wielding a sui generis, some said anachronistic, yet surprisingly adaptable style, both solo and with backing. On Burnin’ the band consisted of the legendary Motown Records studio unit the Funk Brothers, and the results stand amongst the strongest full-length recordings in Hooker’s extensive discography.

In September of 1945 Joe Liggins and His Honeydrippers scored a smash hit on the R&B charts with “The Honeydripper, Parts 1 & 2,” hitting #1 in September and staying there into the following year (18 weeks in total). Heard today and considered in the context of its time, the song’s modernity still shines: WWII is over, and with it comes a sense of optimism only encouraged by a record industry, unshackled by the ban on pressing 78rpm discs, that was cranking out musical advancements recently honed on bandstands, and as the war raged on, mostly heard via airchecks.

In September of 1945 Joe Liggins and His Honeydrippers scored a smash hit on the R&B charts with “The Honeydripper, Parts 1 & 2,” hitting #1 in September and staying there into the following year (18 weeks in total). Heard today and considered in the context of its time, the song’s modernity still shines: WWII is over, and with it comes a sense of optimism only encouraged by a record industry, unshackled by the ban on pressing 78rpm discs, that was cranking out musical advancements recently honed on bandstands, and as the war raged on, mostly heard via airchecks.

Flash forward to 1949, and John Lee Hooker hits #1 on the same chart with “Boogie Chillen’” (remaining at the top for only one week, but staying on the chart for 18), the debut release by this renowned bluesman, featuring Hooker solo on electric guitar in a wildly intense update of the rural “country” blues, the song’s rhythm produced by Hooker’s own foot stomping on a piece of plywood.

Hooker wasn’t the only artist to update and mutate downhome blues styles with amplification and harder and sharper edges and angles (see Muddy Waters, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Howlin’ Wolf, and Sonny Boy Williamson), but he was amongst the most uncompromising in how his style developed. Simultaneously a groundbreaker and a throwback, Hooker’s early success in an undiluted style helped to establish that any changes he made were on his terms.

As R&B and electric blues became ever more refined over time, Hooker resisted, though he did progress in his artistry. Sometimes solo, on other occasions with a band, and around the turn of the 1950s into the next decade, alone and acoustic as he (and associated record labels) sought listeners that were clued in to the burgeoning folk boom.

Instead of unplugged and unaccompanied, Burnin’ pairs Hooker with one of 20th century music’s more belatedly celebrated bands, the crucial Motown Records’ studio outfit the Funk Brothers, who on this recording consisted of guitarist Larry Veeder, bassist James Jamerson, drummer Benny Benjamin, pianist Joe Hunter, and saxophonists Andrew “Mike” Terry (baritone) and Henry Cosby (tenor).

Burnin’ opens with “Boom Boom,” which climbed to #16 on the R&B chart in 1962 and was soon to reside amongst Hooker’s signature songs. It’s also likely the tightest song Hooker recorded, and likewise Burnin’ overall. Heard today with full knowledge of the participants, many will surely assess that The Funk Brothers worked their magic and managed to tighten Hooker up, but nah.

All due credit to the Funk Brothers, but let’s accept that Hooker understood how tightness was a necessity given the start-stop-start nature of “Boom Boom” (he wrote it, after all) and additionally quickly sized up the talent in the room. And some will no doubt assume that the nod to The Champs’ “Tequila” at the beginning of “Keep Your Hands to Yourself” is a byproduct of the Funk Brothers participation in the session, but considering that a portion of Hooker’s vocal in “Boom Boom” sounds a little like Clarence “Frogman” Henry, I wouldn’t be so sure.

In terms of subject matter, Hooker is his reliable self here, railing against fancy hairstyles (“Process”) and makeup (“Drug Store Woman”). It’s really no surprise he has relationship troubles (“I Lost a Woman” and “I Got a Letter”). Above all, Burnin’ is testament to the sheer adaptability of a personal style that far too frequently was spuriously believed to have just oozed out of Hooker unchecked. A fresh listen to this set (available on CD in both stereo and mono mixes with a bonus alternate take of “Thelma”) reinforces how cognizant and consummate an artist John Lee Hooker actually was.

GRADED ON A CURVE:

A