BY MARK SWARTZ | My literary orientation tilts me toward a certain type of song. No doubt, there’s a certain genius to a great Hair Metal ballad or country weeper, but the pop mode that appeals to me most is bookish and clever, with the pros and cons that the latter adjective connotes. Bob Dylan of 1966-1974 is the genre’s Zeus, with Leonard Cohen, Paul Simon, Joni Mitchell, Lou Reed, Elvis Costello, and David Byrne all firmly in the pantheon. Bill Flanagan’s 1987 collection of interviews Written in My Soul canonizes most of them.

Stephin Merritt is probably Generation X’s greatest exponent of literate pop. Principally known for his work with the Magnetic Fields, Merritt also leads the Gothic Archies and the Future Bible Heroes, and some of his best songs are on the two albums by the 6ths that feature a rotating cast of vocalists.

The first Magnetic Fields song I encountered was a 45 I picked up in 1996 on the strength of the cover. The couplet that led off the chorus hooked me immediately.

All the umbrellas in London couldn’t stop this rain.

And all the dope in New York couldn’t kill this pain.

In sharp contrast to most songwriters, Merritt eschews confession in his lyrics. Instead of autobiography, he offers this canard to a potential pick-up:

Papa was a rodeo

And Mama was a rock ‘n roll band.

I could play guitar

And rope a steer

Before I learned to stand.

Over time the band played a significant role in the sound track of my romantic life. My wife was already a big fan before we met, even before their masterpiece 69 Love Songs was released, as were two previous girlfriends. Considering the band’s relative obscurity and the significant differences among these three women, that says something about me.

What does it say, exactly? Perhaps that I permit myself to indulge in extravagantly romantic feelings as long as I do so knowingly—with a wink and a dose of self-deprecation. And that’s the balance that Stephin Merritt achieves better than anybody. Lines like “So you quote love unquote me” and “Under more stars than there are prostitutes in Thailand” aren’t just witty, they are, thanks to a melodic sensibility up there with that of Stephen Sondheim or Burt Bacharach, incredibly singable.

In addition to cabaret-type singers like Curtis Stigers, artists like the Shins, Arcade Fire, Sam Phillips, and Peter Gabriel have covered his songs, but many more should follow their example. (Are you listening, Madonna? Diana Krall? Rufus Wainwright?)

At first I didn’t know what to make of Scott Fagan’s out-of-the-blue e-mail. “I see that you ‘help organizations tell their stories,’ and I wonder if you might be able to help tell mine?’ he wrote. It seemed like some kind of new phishing scam. But before deleting, I googled the name of the sender.

Scott Fagan had a few hits in the early 1960s. According to Wikipedia, he co-wrote Broadway’s first rock opera. And according to his own website, he was Stephin Merritt’s father. My wife had doubts, but a little more research seemed to confirm paternity.

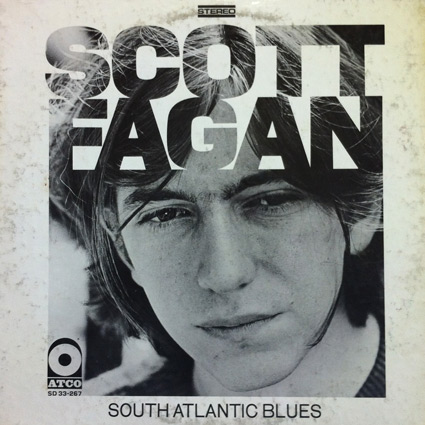

There was another serendipitous cultural connection. Fagan’s 1967 LP South Atlantic Blues was the subject for three artworks by Jasper Johns, all titled Scott Fagan Record. I had written my MA thesis on Johns in the early 1990s and mailed it to the artist’s gallery. A few months later I had gotten a personal letter back, thanking me and noting, “I don’t usually comment on these things.”

Jasper Johns was how Fagan had found me. I had posted, without comment, an image of Scott Fagan Record on my Tumblr, and he had come across it while googling himself.

I called Fagan and found out more of his story. He told me about knowing Jimi Hendrix when he was still Jimmy James and about taking the ship Success from St. Thomas to New York City in 1964. When he arrived, he found a pay phone and dialed a number that a friend of his mother had given him, the number of someone in the music business.

That someone turned out to be the legendary songwriter Doc Pomus, who signed Fagan upon hearing his voice. In fact, Fagan told me, it was at the premiere of the 2013 documentary AKA Doc Pomus that he met Stephin Merritt for the first time. The Lincoln Center premier was hosted by Pomus’s daughter, Sharyn Felder.

Fagan told me he was bowled over when he heard the Magnetic Fields. “It was like hearing songs that I had written and forgotten about,” he said.

He asked me to become his manager, and I declined, but I couldn’t pass up the chance to befriend someone with a connection to both Jasper Johns and Stephin Merritt (and Doc Pomus! And Jimi Hendrix!) A few days later, I got in the car, GPS pointing to a club called Legends in Lebanon, PA. I was hoping for a burger and beer as a reward for the 2.5-hour drive from D.C., but Legends was a couple of degrees less glamorous than the small-town bar I expected, with mismatched furniture and too-bright lights.

No burger, no beer, but there was a snack bar that served a surprisingly delicious turkey wrap. The 10-12 members of the audience included a woman slouched over in a wheelchair, another with ace bandages on both wrists, and a guy with a walker (tennis balls on the feet). Even the sound guy had his foot in a splint. What was this? Legends… of the Fall? In fact, Legends wasn’t a bar at all but a café attached to Calvary Chapel, which serves homeless and disabled people.

The performance itself was terrific. Thanks to a shaggy gray beard, Fagan looked older than sixty-eight, but his voice was still youthful and commanding. The set was all original songs, except “Sloop John B,” which he dedicated to me.

Fagan and I talked more after the show, and I agreed to create a Kickstarter to fund an unprecedented (I think) tribute album of a man interpreting his son’s songs. (Rest assured, I have no financial interest in the Kickstarter or in Fagan’s career, though I was tickled when Johns contributed $500. In exchange for my creating the Kickstarter, he agreed to play a benefit concert in D.C. for Ayuda, an organization that helps immigrants. My wife is on the board.)

The coincidences between the father and son, who never met until a few months ago, might raise some eyebrows but probably fall short of uncanny. Fagan has a daughter named Holiday. The Magnetic Fields have an album named Holiday. Fagan has a son named Archie. One of Merritt’s side projects is the Gothic Archies. Fagan was an alcoholic for years. Merritt writes his songs in bars and constantly refers to liquor in his lyrics.

A 2008 paper published in The Journal of Medical Genetics identified “a genetic contribution to musical aptitude,” but further study is required before scientists understand whether anything more that aptitude—say, a distinct rhythmic or melodic sensibility—is transmitted for parent to child.

Fagan’s father and grandmother were singers. He was born in New York City on 52nd Street in 1945 and moved to St. Thomas as a young child. At eighteen, he was homeless and singing in a band called, appropriately, the Urchins. It was around this time that he struck up a romance with an older woman in the midst of a divorce.

“We lived a very bohemian life,” he recalls. “First in a once beautiful but closed hotel, the Flamboyant, and then on a very picturesque houseboat.” The girlfriend returned to the States, Fagan’s music career began soon afterwards, and they lost touch before their son was born.

On Valentine’s Day 2000, one of Fagan’s ex-wives happened to be listening to NPR’s Fresh Air when Merritt made an appearance, promoting 69 Love Songs, and mentioned his father’s name. The ex-wife called Fagan, and he soon tracked Merritt down via e-mail. As far as I can tell, their relations have been cordial but not close since then.

To what extent has Fagan influenced Merritt, other than genetically? Merritt is a willfully eclectic songwriter, drawing upon virtually every popular musical style of the twentieth century except possibly for hip-hop, which makes the question of influence particularly thorny.

In instances like this, the best course may be to ask the mom. This is how Linda “Alix” Merritt, who raised Stephin by herself, responded to my e-mail query:

Stephin and I learned that Scott had produced a few albums and even a Broadway musical, but we never saw or heard the albums until he found them himself. Stephin was always aware of Scott’s connection with Doc Pomus, and we knew many of Doc’s songs. Stephin’s literary genes and tastes were from me. The musical genes are from Scott, I imagine.

What did they listen do during Stephin’s early years? Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Judy Collins, and classic rock. Asked to elaborate on the “literary genes,” she listed Shakespeare, Shaw, and Ionesco, adding, “I guess we both enjoy art that mocks conventional attitudes, that breaks taboos.”

I believe that Fagan’s sense that Merritt’s music distantly echoes his own is more than an old man’s vanity. I hear it in “Queen of the Savages,” a bouncy tropical ditty from 69 Love Songs, and in the nursery rhymish “Lindy Lou” from the second 6ths CD. Above all, though, I hear the influence working retroactively, in the tender resilience of Fagan’s voice when he sings “Grand Canyon”:

If I was

The Grand Canyon,

I’d echo everything you say.

But I’m just me.

I’m only me.

And you used to love me that way.

For more information on the Scott Fagan Sings Stephin Merritt Kickstarter, please visit the support page. Information on Scott Fagan’s Benefit Concert performance at Ayuda in Washington, DC can be found here.