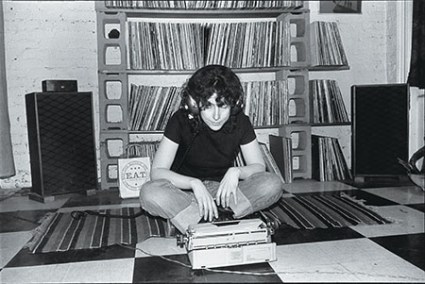

When Ellen Willis was hired by the esteemed New Yorker magazine in 1968 to write about the seminal rock scene she became the first woman to cover the new style of music reverberating across the country.

Though extremely well respected by her peers at the time, she fell off the radar of music lovers in the ensuing decades. A new compilation of her work, Out of the Vinyl Deeps—Ellen Willis on Rock Music makes this important writer’s work available to a new generation.

Though I was very familiar with her better-known colleagues at publications like Rolling Stone, Creem and the Village Voice, I had never heard of Willis until I read about the new book in the New York Times Book Review. I devoured this collection of columns from the New Yorker, liner notes and longer pieces that appeared elsewhere during the heady period when rock went mainstream. She wrote about music from 1968 until 1974. plus a few special pieces that appeared in the 1980s and 1990s, but spent the rest of her career as a feminist theorist, author and teacher. Willis died in 2006 and her daughter edited the collection.

Several things stand out starkly. First off, is her writing itself. This woman was deep. Her vocabulary alone had me running for my dictionary (actually just googling each unfamiliar word). Her sentence structure often boggled my mind as she carefully articulated the nuances in the word play of Bob Dylan or opined on the role of race and sex in the music of the Rolling Stones.

I underlined certain passages because what is most impressive about this work is the fact that she was developing her theories about the sociological and cultural implications of the societal revolution that occurred in the 1960s while it was happening. She was there and she speaks her mind in a fashion that has become increasingly uncommon in the music press. She eviscerates the capitalists (her word) who organized Woodstock in a scathing piece that appeared just a month after the landmark festival in 1969. She reviewed landmark albums like Dylan’s Blonde On Blonde shortly after their release and analyzed the effort as if years had already passed.

Much of the book focuses on her big three musical icons—Dylan, the Stones and Janis Joplin. But she writes compellingly while discussing lesser-known acts including several that I had never heard of before. She weaves her narrative by blending academic discussion (at a time when most scholars dismissed rock as just another fad) with personal anecdotes. Her piece on the Newport Folk Festival when it first started including electric instruments is spellbinding for its prescience and humor.

Of particular interest to festival fans is her commentary about the varying sensibilities between those fans who want to dance and those that prefer sitting. For this reader, who has spent nearly two decades railing against the “chair people” (my coinage), it was telling to read that the clashes between the two different mindsets are nothing new.

Much of Out of the Vinyl Deeps is tough reading. You may feel like you are back in college struggling through dense language and challenging concepts. This is not an easy read like most of what passes for music criticism in the country today. But it is very rewarding and worth taking the time to appreciate the nuances of her writing. Willis weaves a rich tapestry that presents an important era in rock music in a unique light.